In Assembly on Monday morning I asked the children and staff who finds feedback and criticism hard. Predictably, a sea of hands went up into the air. Acting on feedback and criticism is hard and one of the most challenging aspects of developing a growth minded approach.

Inside Out – Riley Argues with her Parents Scene

Our weekly themes this term have focused on the Big Tree Attributes, and this week, linking with Children’s Mental Health Week, is being Growth-Minded.

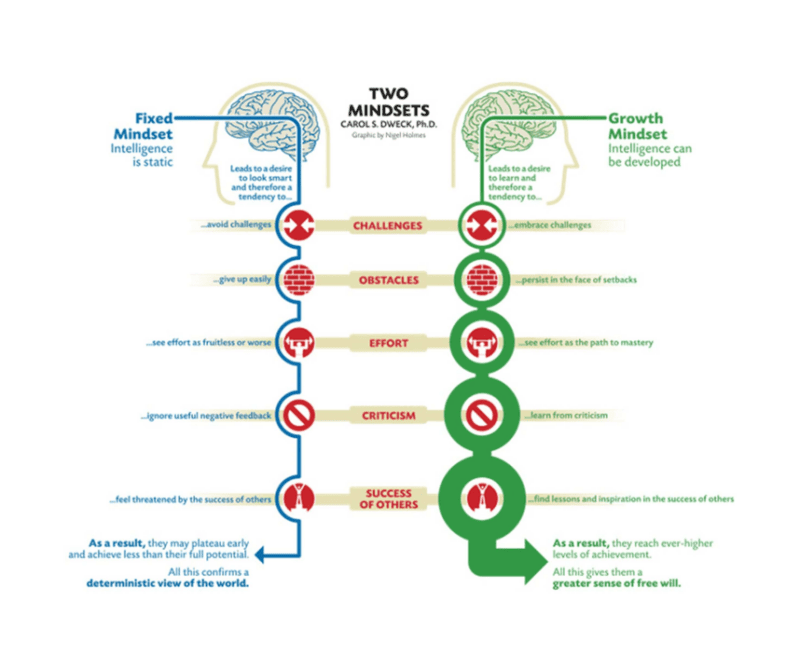

Pioneered as a key educational facet by the American Psychologist, Carol Dweck, in the mid 2000s, the notion of Growth Mindset is an easy concept to understand, yet far harder to enact daily. The block? A fight, flight, freeze mechanism that has been built into humanity from the earliest of times. This instinctive reaction to threat challenges the very notion of developing a growth mindset, yet as Carol Dweck’s research – outlined in her book, Mindset, promotes having a growth mindset as a key driver to success. This is due to the elasticity of the brain, and given what we know about cognitive development now, it makes sense that performance is just as much about our mindset as it is innate ability.

Carol Dweck’s research into Growth Mindset is seen as a seminal moment in what we know about a young person’s cognitive development.

The notion of having a growth mindset was always to be a central pillar in the ‘Big Tree Learner Attributes’. If our mission is for young people to enjoy a soaring performance, then they must have the right mindset to achieve this.

And, as illustrated in the diagram above and video, here, Growth Mindset vs. Fixed Minds

There are many facets to achieving a growth mindset.

The one that I feel is perhaps the hardest, but most important, is about being able to take on feedback and constructive criticism. Emerging from the research used in assessing elite performance of sportswomen and men, this is often referred to as coachability.

Established author, Matthew Syed, knows more than most about the role feedback plays in achieving growth and success. In his best-selling book, Bounce, he talks of, “The way we engage with feedback, how we handle setbacks, and whether we see mistakes as learning opportunities or threats, determines our capacity to grow.”

He doesn’t simply note the importance of taking feedback well but actually doing something with it to drive growth, and this is where our focus will lie at Packwood. In the context of increased automation, leading to reduction in jobs, employers are seeking applicants who can act on feedback and therefore grow in their capability. But there’s another reason for this focus, and it lies in two of the most powerful words associated with growing up: self-esteem.

This week is the charity Place2Be’s annual mental health awareness week. Their theme this year, based on the characters of Disney’s Inside Out, is know yourself, grow yourself.

Significant research going back twenty-years makes the links between acting on feedback and the development of motivation, self-efficacy and heightened wellbeing. There is also research to back up the notion that overly excessive and negative criticism, however well intentioned, does much to damage the recipient’s self-efficacy and wellbeing.

However, a person must have the grounding, emotional regulation and self-worth to receive and act on feedback to grow. The children at Packwood are right in the middle of their formative years to develop their emotional grounding and equilibrium to have the capacity to take feedback and then act on it. Without this, at best feedback falls on deaf ears; at worst it leads to distress and anxiety.

Where does this responsibility lie then? Within the many conflicting demands of parenting and bringing up children, we can be forgiven for seeing this as yet another burden for our children and us.

Here are four relatively easy strategies to frame the right language in ensuring our children take on feedback and then act on it:

- Praise effort over attainment. “I can see you tried really hard with this” is more powerful than, “you’re so clever”. The former focuses on growth mindset and leaves room for further growth; the latter puts a ceiling on any further improvement. Fear of failure is averted in the former, cemented in the latter.

- Use the classic teacher method of, ‘what went well; even better if’: “you played that piece with real expression, and I could see your personality come through. Let’s try and work on the dynamics to bring about greater contrast”. Feedback is given with a goal for further growth. It is non-confrontational and encouraging.

- Always correct a child when they verbalise negative self-talk, such as “I’m terrible at maths”. By accepting this, we are validating their feelings. Reframe this with them to, “I’m still getting better at maths”.

- Celebrate mistakes. We are so afraid of our children ever making mistakes. Once this mindset sets in, no form of appropriate feedback will ever make up for the perceived catastrophe of getting something wrong.

Our newly introduced mentoring approach at Packwood (still in its trial period) focuses on these four key areas. It is developed to both develop self-esteem and encourage those who have yet to perform at their very best to accept nothing but their best selves.

As Joy says in Inside Out 2, “You can’t focus on what’s going wrong. There’s always a way to turn things around.”

Inside Out 2 – The Creation of Riley’s Sense of Self – YouTube